NATIONAL ARMY MUSEUM, LONDON: A MODERN LOOK AT AN HISTORIC ARMY

- Sarah

- Dec 6, 2020

- 10 min read

Updated: Mar 2, 2021

The National Army Museum in Chelsea is the central hub of all the British Army museums, as others tend to concentrate on just one regiment or corps. Starting with its formation during the English Civil War, the museum looks at the experience of soldiers over the centuries, up to the present day.

Built on the site of the former Infirmary for the Royal Hospital in Chelsea after it was bombed during World War II, the museum is situated on Royal Hospital Road in Chelsea, in a brutalist modern building designed in the 1960s.

Opened in 1971 and recently having undergone a massive refurbishment, the museum was reopened by the Queen in 2017, with a new focus on creating a dialogue about the army, exploring its purpose and looking at its relationship with the general public.

The museum is divided into five galleries, Soldier, Army, Battle, Society and Insight. So engrossed were we at the start of our visit, after two hours we were not able to do the Army Gallery justice, and had to skip the Insight Gallery altogether so we didn't miss our train home. My first tip for visiting the National Army Museum then is make sure you have ample time – three hours if you want to see all five galleries thoroughly.

NATIONAL ARMY MUSEUM - SOLDIER GALLERY

The Soldier Gallery is the best place to start. At the entrance you are confronted immediately by the question “Could you be a soldier?” written above the doorway, and you chose which side to walk through, yes or no.

I blithely sailed on through the ‘yes’ doorway, making all sorts of excuses for myself that of course I could join up if I was younger, fitter, more compliant. Throughout the exhibits you are then invited to reconsider your answer in the light of the lifestyle and discomforts of soldiering along with the fear and reality of combat.

The gallery leads you through the various stages of recruitment; that of the early press gangs through to wartime conscription and National Service, and all that this entails in terms of medical and physical assessment and the commitment made by every soldier. Recruitment posters cover the walls, an enticing display of travel, camaraderie and adventure, offering viewers to ‘see the world and get paid for doing it’.

L: This glass bottomed tankard from 1862 meant that people could check if they had been tricked into joining the army and see if the King’s Shilling had been slipped in their drink.

R: This tiny jacket would have been worn by a 5 year old drummer boy. For sons of soldiers, sometimes the army was the only family they knew.

In the display about the press gangs is a glass bottomed tankard, used by men who wanted to ensure that they hadn’t been slipped ‘the King’s shilling’ which was how people could be unwittingly conscripted into the army.

There are exhibits asking why people would sign up, what their motivations were. For some it was family tradition, others were escaping poverty at home, others were looking for adventure or employment, and in this respect, not much seems to have changed over the centuries.

We then get taken through the selection process; the medicals and tests, the kit and the total upheaval in their lives. Next came intensive and rigorous training, what they had to do to get up to scratch for the British Army. An amusing interactive screen puts three visitor recruits literally “on the spot” to be drilled by a fierce Sergeant-Major who barks out orders, encouragement and contempt accordingly. As ‘Recruit 3’, I found myself being bellowed at for not marching in time, much to the entertainment of those around me.

L: Guns used over the centuries and the training time required to learn how to use them. At the bottom is the ‘Brown Bess’ musket which took 10 weeks training in 1727. At the top is the Lee-Enfield, used in 1940 and which took 18 weeks to learn how to use.

R: Orders and commands were given to solidiers through drumbeats, which were ‘drummed’ into them during training.

Exhibits such as training sticks that measure a recruit’s step, drill medals to motivate them, awards for the best shot and a large wooden spoon for the worst, show how seriously the recruits were expected to take their training, and how the army has managed to maintain the highest standards possible.

Soldiers would use these blocks to enact the large scale, complicated manoeuvres they had to perform together. Using these blocks, which date from 1803, would help them to practice the theory beforehand.

There is then a look at life in barracks, and in the field, with comments by soldiers from the 18th century to the present day on their overall experience. The discomfort and boredom is clearly demonstrated, along with the strong sense of comradeship and reliance on those in the same unit. Many of the comments focus on how the experience has shaped their lives, often in terms of their friendships gained and loyalty to their comrades.

Exhibits include rules of the mess, mess dress and some of the items used in the soldiers’ leisure time, including a decanter set made from an elephants foot, one of their hunting trophies.

We learn about their diet, the differences over the years, what they ate and what was considered a good meal, for after all, an army marches on its stomach.

A section on health shows us how they exercise, the sports they do, the educational programmes they undertake, and their hobbies. We see how this has developed over the centuries, from their chief vices being drinking and gambling to now, when the army produces Olympic athletes.

This rather awful looking device was used to brand deserters with the letter ‘D’ so that they were permanently marked and shamed. This was used in the early 19th century.

There is a section on punishments used on unruly soldiers, for everything from drunkenness to desertion. Some of these seem very brutal to modern eyes, but is how the army was able to maintain discipline, which was vital during times of war

To hammer the point home that serving your country is not about glamour but often about sheer terror, injury, misery and death, there is an audio-visual section which seeks to demonstrate, not through horrific battle scenes, but through dramatic sound and colour, the reality of war.

As you sit in the dark watching these fractured screens, you can’t help but feel a glimmer of understanding of what many of them must go through.

Could you be a soldier? Walk through the exit ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to make your decision, and compare it to that of other visitors

The visitor is left with a head reeling with thoughts and dilemmas and, on exit, is asked the question again “Could you be a soldier?” I hesitated this time, now knowing full well that it was a lot more challenging than I had thought, and even if I was younger, fitter and obediently did what I was told, I still would have struggled. Interestingly, the statistics show that at least a third of people who cheerfully answered “Yes” on the way in have changed their minds by being forced by the exhibits to consider the practical and moral questions associated with army service.

NATIONAL ARMY MUSEUM - THE BATTLE GALLERY

We visited the Battle Gallery next, a fascinating look at the actual warfare the military engage in, which includes an incredible section on Waterloo. A huge diorama of the battle site is laid out, with a video explaining the course of the battle, and some interactive screens for people to delve deeper into the history of it. There are some amazing artefacts, such as the skeleton of Napoleon’s horse, Marengo, which was captured by the British.

Napolean’s famous war horse, Marengo was injured eight times in his army career, until he was captured at Waterloo. He spent the rest of his years in the UK, eventually dying of old age. The horse lived for a further 16 years before it died at the grand old age of 38.

There is a standard, captured at Waterloo by a squadron, who hacked their way through the French just to get to it. Wellington’s famous hat and cloak are on display, as well as a note written in his own blood by a soldier. A saw, used to hack through the Earl of Uxbridge’s leg sits next to the bloodstained glove which was used to stem the blood flow during the operation.

L: “I am shot thro the body – for God’s sake send me a surgeon, English if possible” – the last note written by Joseph Fenwick and in his own blood. He died shortly afterwards.

R: The saw used to amputate the Earl of Uxbridge’s leg at Waterloo, and the glove and handkerchief used by his aide to stem the blood. The Earl apparently remained composed throughout, merely commenting that the saw seemed ‘a bit blunt’.

The exhibition moves on through the Crimea, the Boer War and two world wars – and includes some weaponry and machinery – but this is not where the emphasis lies. Questions are written on the walls to really get the visitors to think about the role of the army and warfare: What constitutes a good cause? What is the fine line between questioning and torture? Should we use anti-personnel mines if it means fewer people will die? Is any weapon justified if it shortens a war?

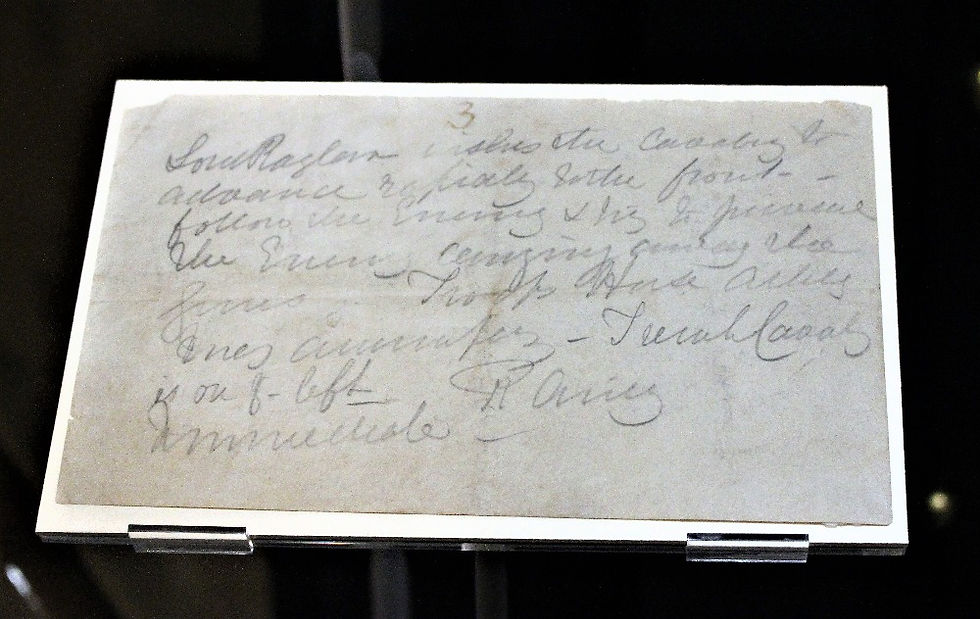

This is the actual order that initiated The Charge of the Light Brigade in 1854. Misunderstanding its meaning, the British suffered a 40% casualty rate, losing 278 men and 375 horses.

There is an interactive display where you can practice firing and reloading a gun, to see if you can do it quickly enough. Unlike my feeble attempt with the drill sergeant, I was pleased to actually be able to do something right, and quite got into the swing of firing, reloading and firing again as fast as I could. This seemed to be a popular activity and there were plenty of people having a go.

NATIONAL ARMY MUSEUM - THE SOCIETY GALLERY

The Society Gallery looks at the army in modern day society and shows how the truth about conflict has often been distorted by films and the media. Posters of war films cover the walls in an incredibly visual display, showing films used for propaganda, films which glorify war and films which show the horrors.

The portrayal of soldiers in films and books says a great deal about society’s relationship with the army and have a big impact on how people feel about them. The question is asked, do these portrayals reflect society’s attitudes, or does it shape them? Visitors are invited to use an interactive screen with a questionnaire about how they feel about aspects of the army, thought provoking questions that really make you think, with the illuminating results of others shown to you afterwards.

A section on army medicine follows, with exhibits such as one of Florence Nightingale’s lamps, a military doctor’s medical bag, and a look at how army medics have developed medical care that is still is use worldwide. Pioneering surgery on those maimed and deformed in World War I is still relevant, and military medicine is at the forefront of new developments that help so many others, not just the armed forces.

L: Florence Nightingale used this paper lantern at the military hospital at Scutari during the Crimean War of 1854 – 1856. She instigated pioneering work in nurse training, cleanliness, triage and the use of medical statistics, being the first to use pie charts to clearly explain medical data.

R: Harold Gillies was the military surgeon who pioneered reconstructive surgery. Here, artist Paddy Hartley has stitched the surgeries of one of his patients, Walter Fairweather, onto a World War I uniform. Walter had gunshot wounds to the nose and eye in 1916, and this is the list of operations and surgeries he had to have.

A display looks at the act of remembrance and the use of poppies, looking at how the wearing of poppies started and how it has changed over the years. The various different types are on display, and exhibits discuss the controversy of poppies which still rumbles on today.

The gallery moves on to the ‘Age of Intervention’ – people protesting the use of the army in war, demanding that troops are returned home, with protest posters from recent wars. The walls deliberately give opposing messages, mixing propaganda and recruitment posters with campaigns against militarism, calls for demonstrations against specific wars, asking a series of significant questions about such topics as the treatment of prisoners of war, the role of politicians, the right to disobey either incompetent or immoral orders.

NATIONAL ARMY MUSEUM - THE ARMY GALLERY

Due to time constraints, we only managed a quick peek at The Army Gallery, which explores the reasons why we have an army and its origins during the turmoil of the Civil War, which was when England had its first peacetime professional standing army.

Previously, armies had only tended to fight in a specific area or garrison, and were raised as a militia. The New Model Army was the first professional army that would travel across the country, and when the Civil War was over, it was disbanded and the monarchy was restored, Charles II kept up a standing army.

This gallery includes uniforms of some very famous people, from the Queen’s during World War II to Lawrence of Arabia, one of the most famous of all modern soldiers. There are exhibits from the Civil War, a look at regiments and the ranking system, and children get a chance to design their own cap badge.

WE RAN OUT OF TIME …

Sadly, we didn’t visit the Insight gallery at all, as we had to catch a train back home. The exhibits in this gallery explore the role of the Army today, the conflicts they are involved in and where they still have strategic interests. The displays here change regularly and currently focus on Germany, Ghana, Scotland amongst others.

I was extremely impressed by this museum. It’s fantastic for children because the information panels are short, clearly written and attractively presented, and there are plenty of interactive activities, most of which are fun and all of which are engaging.

And for adults there are not just the exhibits, but difficult questions to be contemplated. It takes a balanced and comprehensive stance towards its subject matter, with none of the “death or glory” attributes often associated with regimental museums.

Instead it offered a thorough and sobering look at the British army through the ages, concluding by considering the place of a modern army in a democratic society, with a series of challenging and uncomfortable questions that really make you think.

And – what is truly impressive – it’s all free!

VISITING THE NATIONAL ARMY MUSEUM

Getting to the National Army Museum

The entrance to the museum can be found on Royal Hospital Road.

what3words: trip.cool.crops

Nearest underground stations: Sloane Square (10 minute walk), 20 minute walk from Victoria Train Station.

Opening Hours

Daily 10am - 5.30pm

Closed on the following days: 24 – 26 December and 1st January

Ticket Prices

Free

Facilities

Gift Shop, Cafe

Very child friendly with a play area and plenty of kids activities

The site is fully accessible.

MILITARY HISTORY ITINERARY OF LONDON

For those who are interested in military history, you will know there is a lot to see in London. We have created an itinerary that takes in the sites and memorials within central London, all of which can be visited on a single day. Given its historical significance as much as the quality of the museum, the National Army Museum is included on this itinerary, along with the Royal Hospital Chelsea and the Household Cavalry Museum.

Comments