A VISIT TO DORCHESTER PRISON

- Sarah

- Jan 24, 2022

- 7 min read

Updated: Feb 5, 2022

Closed in 2013, Dorchester Prison is now awaiting its fate from developers, who will be turning the site into luxury flats. In the meantime, this historic Victorian prison is open for guided tours from a Prison Officer who worked there until it closed, providing a fascinating insight into the life of a county prison.

Dorchester Prison was once a focal point for the county town of Dorset, receiving men from the Crown and Magistrates Courts in Dorchester, Bournemouth and Poole, holding a mixture of both convicted and remanded prisoners. It was built in 1885 on the site of an older prison which had been built in 1796 and demolished around 1880, which in turn was constructed on the site of a castle from 1154.

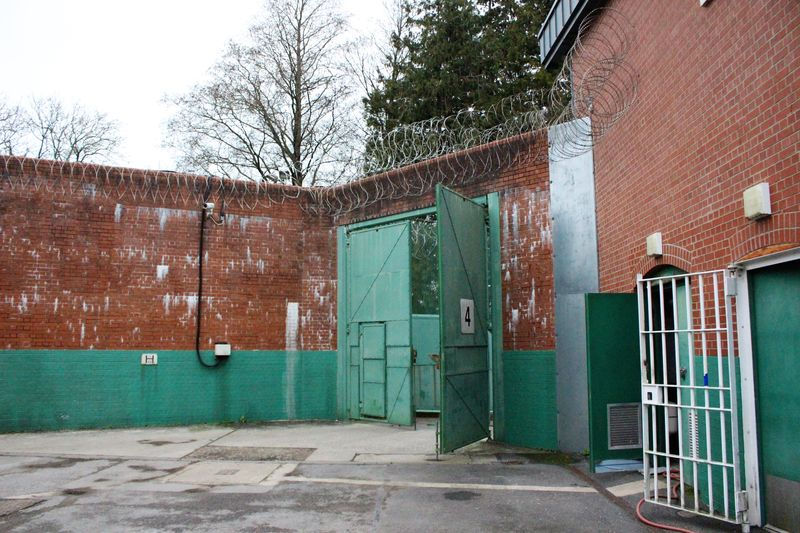

Like many Victorian prisons, it was designed with wings radiating from a central area with galleried landings. Constructed in red brick with barred windows, towering chimneys, huge steel gates, razor wire everywhere and surrounded by a tall, thick wall, the prison is a relic from an outdated penal system.

While the building rots and rusts quietly as its future remains uncertain, the prison is open for guided tours, paranormal nights and combat games. I joined a tour yesterday on a bitterly cold January day, to have a look around.

Tours at Dorchester Prison are conducted by the very personable Ed who is still a serving Prison Officer in a nearby jail and who worked for ten years at Dorchester Prison before it closed.

On arrival you sit in a large room upstairs, all institutional sour-pink walls, overly bright plastic seating and sagging sofas, with corporate silver tea urns, waiting until the tour group is assembled.

Our tour had 29 people on it, a mixture of people who were fascinated by what lay behind the thick walls, a group of women with selfie sticks who I think had once worked there and even an ex-inmate who had spent some time there at Her Majesty's Pleasure.

Our tour started outside, where Ed stood on the steps and introduced himself while we stamped our feet and rubbed gloved hands in the ice cold air underneath a white sky filled with squealing seagulls. Behind us was a clock dating from the turn of the century framed by razor wire, the blue paint peeling and fading under a misshapen cover of lead flashing.

Ed took us around the grounds, a haphazard mixture of Victorian brick, modern extensions and rubble where buildings have been added and removed over the years, as well as recent archaeological excavations taking place in the grounds. Doors and gates led to various unspecified rooms many of which were workshops used for repairing things and which are part of the original 1885 buildings.

Ed stopped next to a blue shutter high on a wall and told us this was once the site of the hanging shed, until it was knocked down and replaced with modern kitchens.

Executions had taken place in public until the end of the 19th century when the appetite for them as a form of entertainment had waned with Victorian sensibilities. After that, executions had moved within the prison walls. Dorchester Prison had nine executions in the past 150 years, the youngest being a 15 year old who was hanged for arson.

At the time it was considered a 'cruel and unusual' punishment to make the condemned walk too long to the site of their execution; many prisons of the time would have the hanging shed right next to the cell. Here in Dorchester Prison, it was a two minute walk from cell to scaffold, which was considered too long. The hanging shed was last used in 1941.

Our walk took us to the exercise yard, a grey concrete square surrounded by grey walls, grey razor wire with two stone benches and a grey pole. Ed explained that the pole used to hold up a net, erected to catch contraband that people on the outside would throw in for the inmates, sometimes hidden in tennis balls. The yard was oppressive with its many shades of grey under the bleak grey, icy sky. Next to it was a smaller space which was used for those in solitary confinement, as they were only allowed to exercise on their own.

There is razor wire everywhere, its dull coils over every wall, gate and surface. Ed told us that type of razor wire is actually illegal in the UK, the only places that are allowed it are prisons who have to pay an annual fine to the government, who actually manufacture it.

Our tour was interspersed with several anecdotes like these, and you can sense the despair at the shambolic bureaucracy which surrounds the prison service. Another example was how items that needed fixing and repair used to be dealt with in the prison workshops - the item would be back to new in an hour or so. After the government's centralisation policy, it could then take weeks for something to be fixed. Similarly, Dorchester used to have its own laundry but that was also centralised, with items being sent off site for cleaning within a central cluster. They would send off hundreds of uniforms, sheets, everything and they would rarely get the same laundry back - one time they sent off a full load of items and got back a single hamper of just socks.

The prison had £41 million spent on it in the 12 years up to 2013, with a brand new healthcare section built just six months before it closed. The waste of taxpayer money was shocking.

Our tour then moved indoors and if we were expecting it to warm up, we were bitterly disappointed. The chill wind may have gone, but there was no warmth within those walls, something the prisoners would apparently often complain about.

Ed took us into the reception room where he talked us through what would happen if we were new prisoners arriving at the prison. He explained the process - how a prisoner would have his clothing removed one piece at a time with each item listed down, and each time be replaced with a piece of prison clothing. Their valuable items would also be itemised and removed, with inmates given one minute to write down all the mobile numbers from their phone that they might want access to during their stay, before they had to hand the phone over which they would not see again until they were released. There were healthcare checks followed by a photo and a prison number. Since 2009 a prisoner can keep the same prison number if they 'choose to make a career of it'; before that they had a different number for each time in prison which could get confusing for all involved.

They get asked dietary requirements as all diets are catered for, given their sheets, bowls, cleaning kits and other necessities before they walk to the centre of the jail with everyone watching from the cells above. It was easy to imagine the fear that many must have felt as we walked into the bottom of that chilly atrium.

The central hub from which the wings emanate is oppressive - high ceilings with bars everywhere we walked; narrow stairs and narrow landings surrounded by rusting bars, there was no need for suicide nets here as even the bars had bars.

We wandered through the landings peering into the cells which were all tiny, with institutional blue, yellow and green paint peeling off the walls in sheets, the black mould spreading across the rooms, the stainless steel loos and sinks, rusting sagging bunk beds and all with just a single pipe running across the back wall, which was their only source of heating.

Ed often mentioned the cold, how the punishment cells were so freezing that they were unbearable and some inmates would have to spend 12 hours in them. We stood there in our frozen group all in coats but still shivering and it was hard to imagine having to live like that.

We went into the chapel, a modern room with artificially bright blue walls and a red glass cross in the window behind bars. The prison service had to provide a minister for the religions of all inmates - even Jedi which is a recognised religion in the prison service. The chapel was used for meetings and all sorts of other events as well as religious purposes.

It was here in 2013 where staff were informed that the prison was closing. They were all very upset, being told that "every jail has its sell by date and you’ve reached yours". Several prisons across the country were closed in one go, saving the Ministry of Justice £3.8 billion from their budget, but leaving the prison service in freefall. The service is still understaffed by 10,000 officers.

We visited the Healthcare Wing where there were pharmacies and medical rooms. It is here where the ghost of Martha Brown is believed to be. As Ed was telling us a few stories of the various hauntings, he slammed shut one of the metal doors, and we all jumped in shock as the noise echoed throughout the empty rooms and corridors.

I found it fascinating to hear from a serving prison officer. I have no knowledge of the prison system, any information I have is from TV shows and films, so I was surprised how humane the officers seem to be - I imagined them to be brutal and uncaring, but as Ed was telling us about it all, giving us his thoughts on the injustices often meted out to them, I was surprised by his obvious sympathy. Researching this prison I found a website where ex-inmates were saying how they looked back on their time in Dorchester with some fondness, even using the phrase that they were 'good times'. The ex-inmate on the tour held no rancour and was happily discussing past times with Ed and the other people in the group. It reminded me again that the real world is often a far cry from how it is portrayed in fiction.

The tour was excellent - enlightening, fascinating and educational and is one I highly recommend before the prison is turned into flats and the chance is lost forever.

Visiting Dorchester Prison

Book tickets (£15 each) on the Gloucester Prison tour website (they own both prisons)

The tour is about 90 minutes long

There is free parking on site, but the prison is very central and can easily be reached by train and bus with just a very short walk

Want to visit more old prisons? Try one of these 13 prisons you can visit in the UK

Comments